John Schneider, Cincinnati’s “Mr. Streetcar” and a co-principal of Urban Rail Today, addresses APTA Streetcar Committee meeting on Dec. 15th. Photo: L. Henry.

♦

Cincinnati, Ohio — Roughly a hundred streetcar planning and development professionals — including Urban Rail Today co-principal Lyndon Henry — converged here in mid-December to attend a business meeting and technical tours sponsored by the Streetcar Subcommittee of the American Public Transportation Association (APTA). The main meetings spanned two days (15-16 December 2014), covering topics ranging from technical issues to the nuts-and-bolts of Cincinnati’s long political saga, navigating through public referendums and electoral permutations to finally secure the streetcar project now fully under construction. A highlight of the meetings was a presentation by John Schneider, Cincinnati’s “Mr. Streetcar” (see photo at top of this post), who chronicled and explained Cincinnati’s convoluted path to a rail transit system. (John is also a co-principal of Urban Rail Today.)

But special tours were also a major highlight of the APTA event, including a Dec. 14th tour of Cincinnati’s “subway-that-never-ran”, the remnants of subway tunnels beneath the center of the CBD. Built after World War I and into the 1920s, but eventually abandoned when city leaders scuttled the project, the subway is a creepy, sad, but fascinating artifact of urban industrial archaeology, with ghostly stairways, waiting platforms, and ticket kiosks constructed for passengers that would never come, and stringers ready for tracks that were never laid and trains that never ran. (Municipal bonds were not finally paid off till the 1960s — a kind of object lesson in the drawbacks of lack of perseverance and excessive misplaced frugality.)

For more information, history, maps, and photos, see:

• Cincinnati’s Abandoned Subway — history and photos

• Zach Fein (Cincinnati architect and photographer) — excellent modern photos

• Cincinnati’s Abandoned Subway — link to PBS documentary available on Amazon.com

APTA tour group walking through darkness of Cincinnati’s never-finished subway on morning of Dec. 14th. Photo: L. Henry.

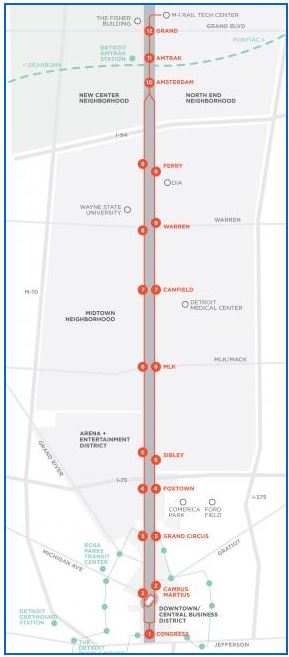

Most of Cincinnati’s modern streetcar starter line project is now under construction, and particular features were inspected via another APTA Streetcar Committee tour on Dec. 16th. It’s a roughly 1.8-mile route, end to end, with about 3.6 miles of track and 17 stations. As the map below illustrates, the route has a sort of elongated “Figure 8” configuration, forming a long, narrow loop with tracks for each direction on parallel streets — no double track.

Map of Cincinnati’s Phase 1 streetcar project, the first phase of hopefully a much larger urban rail system for the city. Map: City of Cincinnati.

In the middle segment where the alignment runs east-west for a short distance, the bottom (southern) track is routed in the median of Central Parkway, and the upper (northern) track along 12th St. Central Pkwy. was constructed atop the site of an old canal, and it was this canal that got drained and converted into the ill-fated subway that never opened.

Cincinnati’s famous Over-the-Rhine (OTR) district is the area above (i.e., north of) Central Pkwy. The district once was home to a substantial population of German immigrants who dubbed the old canal the “Rhine”. The area declined over the many decades since the subway debacle and the rustbelt decline of Cincinnati, but the neighborhoods adjacent and near to the streetcar line are experiencing quite a revival.

Streetcar rolling stock is being supplied by the Spanish railcar manufacturer CAF through their U.S. subsidiary CAF USA. Five cars for the starter line will be the first 100% lowfloor streetcars deployed in America (see simulation graphic below). Each will be 23.6 meters (77.4 feet) long, with four doors per side, 32 seats, and a total capacity of 154 passengers. Up to 6 bicycles can also be accommodated in the car.

CAF Urbos 3 streetcar for Cincinnati. Top: Interior. Bottom: Exterior. Graphic: CAF.

CAF’s Urbos 3 car is actually a fully robust light rail transit (LRT) car adapted for streetcar application. The cars are double-ended (i.e., bidirectional) with a maximum speed capability of 70 km/h (about 43 mph).

As illustrated in the photo below, the streetcar project is being constructed predominantly with curbside tracks and stations that simply protrude outward from the sidewalks.

Members of APTA Streetcar Committee inspect streetcar station-stop under construction on Walnut St. in Cincinnati CBD. Photo: L. Henry.

The photo below shows a completed section of track next to a station in the OTR district. The track diverges slightly toward the station platform, in part to minimize clearance needed for the platform edge and to maximize clearance with respect to the parking lane.

Completed section of streetcar track veers slightly toward station platform. Photo: L. Henry.

The use of recycled cobblestones to embed some sections of the track is shown in the photo below. This kind of treatment (if other motor vehicle lanes are left smooth) may tend to dissuade motorists from excessive running in the streetcar lane, giving it a bit of the quality of a semi-dedicated lane…

Section of streetcar track embedded in cobblestone paving. Photo: L. Henry.

The system’s initial carbarn (storage-maintenance-operations facility) is under construction at the north end of the current route, at Henry St. The photo below, looking south, shows the main building and part of the storage yard. While the system will start with just five cars, the facility has space for 13. The revenue track wraps around on Henry St., on the carbarn’s north side (i.e., behind the camera in the photo below) to effectively reverse direction and head southbound.

Carbarn main building and portion of streetcar storage yard under construction. Photo: L. Henry.

In the photo below (facing north, toward Henry St.), track workers are performing thermal welds on one of the fan tracks leading into the carbarn. The street just beyond them is Henry St., which streetcars will use to turn from northbound to southbound and thus loop around the carbarn.

Workers performing thermal weld on track leading into carbarn storage yard. Photo: L. Henry.

Cincinnati’s streetcar project is clearly not only well on its way, but planners are already scoping out the next extension, reaching further north to the University of Cincinnati. Furthermore, with a system designed for and deploying fully capable LRT rolling stock, an eventual transformation of the basic streetcar system into a faster, high-capacity LRT system is a distinct possibility for the future. ■