♦

Just about anyone who’s raised the possibility of light rail transit (LRT, the most popular form of urban rail) for their community has probably encountered a familiar pitch for “bus rapid transit” (BRT): Why not try “BRT” instead? It’s just like light rail, but cheaper…

The problem with this isn’t that better bus service is a bad idea. Upgraded buses, upgraded bus stops, traffic signal priority, high-tech innovations such as “next bus” passenger information systems at bus stops and onboard wi-fi, and other improvements, are all important ways to attract more ridership to public transport.

But the problem is that a collection of “BRT” promoters — from the motor bus industry to highway enthusiasts to some self-proclaimed transit supporters, have been claiming that, somehow, “BRT” has all the advantages of urban rail at much lower cost. And that’s just plain wrong. It’s false, and in many, perhaps most, cases, it’s deceptive. In effect, it’s a kind of snake oil being peddled in the field of urban transit.

An awful lot of cities and transit systems worldwide that have been vigorously installing new LRT systems (including streetcars) haven’t been ignorant or oblivious to the “BRT” option. Instead, they’ve reviewed and analyzed the pros and cons of this and other alternatives, and concluded that, for their own needs, LRT — and other forms of urban rail — is the best choice.

Let’s briefly consider a few of the most familiar claims that “BRT” proponents try to promulgate.

► “BRT” is truly “rapid transit” — Mostly nonsense. The “BRT” promotion campaign typically presents images of buses on special exclusive guideways (the so-called “Gold Standard” of BRT) to seduce public support (mainly from local civic leaders). But the reality of most purported “BRT” systems is … buses running mostly in mixed traffic like “regular” buses, but perhaps in limited-stop modes, with somewhat fancier stations … but a far cry from fully grade-separated rapid transit.

This has become an issue in Austin, Texas with perhaps the most recently opened so-called “BRT” system (funded as “BRT” under the federal Small Starts program). Called MetroRapid, the system is being widely ridiculed in the community for attracting daily ridership of only 6,000 and resulting in a net ridership loss of 11% in the corridor it serves. See: Why MetroRapid bus service is NOT “bus rapid transit”.

Austin’s MetroRapid “BRT” systems runs in mixed traffic, and has become the object of local ridicule. Photo: L. Henry.

► “BRT” is a lot cheaper than LRT — Well maybe, maybe not. When total lifecycle costs, expressed as annualized capital costs, plus operating and maintenance (O&M) costs are considered, LRT is often the more cost-effective investment, particularly through the essential metric of cost per passenger-mile.

This issue is analyzed in a number of articles on the Light Rail Now website; see, for example:

• Light Rail Lowers Operating Costs

• How Light Rail Saves Operating Cost Dollars Compared With Buses

• Streetcar vs. Bus: Operating cost comparison

• “Free” buses vs. “expensive” rail?

• Brisbane Reality Check: The high cost of “cheap” busways

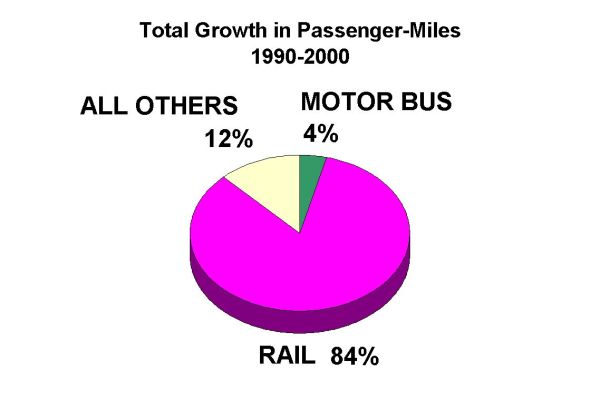

► “BRT” attracts as many riders as LRT — Certainly not on average. Overall, LRT systems beat all types of bus systems in meeting ridership goals and attracting “choice” riders (who have the option of using private motor vehicles). Some evidence is provided in the following articles:

• Rail Transit vs. “Bus Rapid Transit”: Comparative Success and Potential in Attracting Ridership

• Research Study: Riders Prefer Light Rail to “Bus Rapid Transit”

• Motorists prefer light rail over buses, reports UK poll

► “BRT” has the capacity of LRT — Definitely not in terms of ultimate potential capacity. As “BRT” systems attempt to cope with increasing ridership (which may happen not because “BRT” systems are so attractive, but because of rising population and the increasing costs and congestion of private motor vehicle systems), the number of buses required to try to provide capacity starts to overwhelm road systems and station passenger-handling capacity.

Massive bus traffic jam in Brisbane, Australia illustrate problem of fitting “BRT” into a high-capacity application. Photo: James Saunders.

► “BRT” attracts development, just like LRT — False. This claim by “BRT” advocates is based predominantly on cases in Pittsburgh and Cleveland, In both cities, the real estate development attributed to “BRT” was overwhelmingly attracted by rail transit systems, both existing and planned.

► “BRT” is just like LRT, but cheaper — Definitely, totally false. Basically, you get what you pay for. “BRT” fails to offer the speed (for similar routes and station spacing), ride comfort, reliability, accessibility, lower energy consumption, lower environmental impact, cost-effectiveness, and urban livability of LRT. Here are some articles that provide evidence for this:

• New light rail projects in study beat BRT

• LA’s “Orange Line” Busway – “Just Like Rail, But Cheaper?” A Photo-Report Reality Check

There are other issues in this comparison which merit being covered. We’ll examine some of them in future posts. ■